Brazil and Honduras are two countries in which women are taking the lead in stories of self-improvement and resistance against established power in the continent.

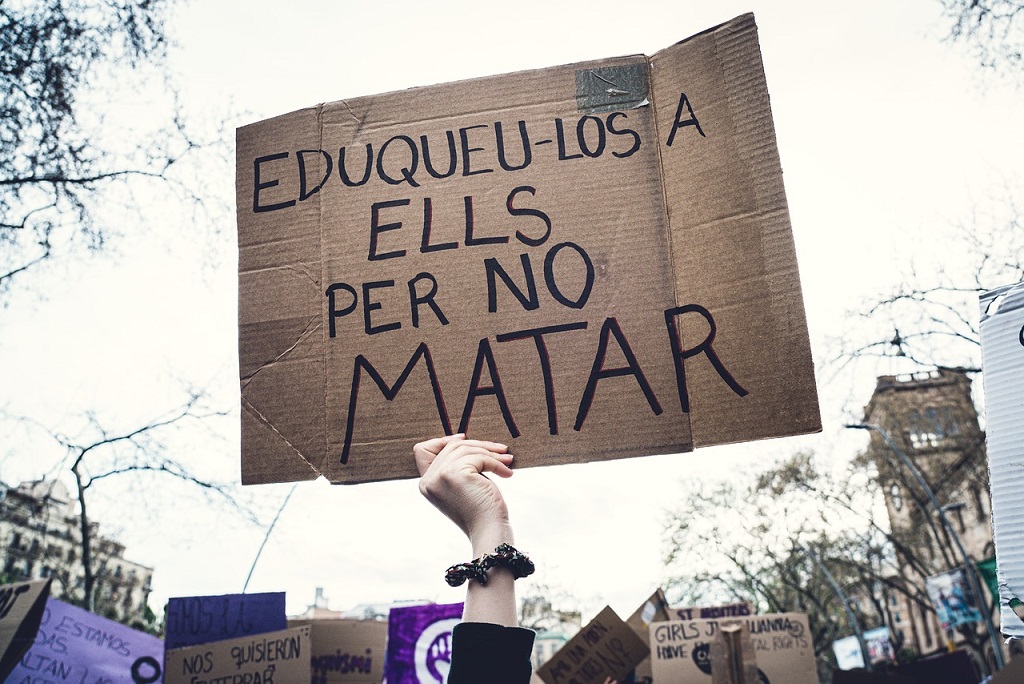

Gender-based violence and femicide, the emancipation of women, female circumcision, universal suffrage, equal pay and work for men and women are some of the issues that arise in different geographic regions.

Those problems occur because in many regions of this planet, women as a community are undervalued, mistreated and ignored, which is what leads them to protest and fight for their rights. This is the case in many Latin American countries, including Brazil and Honduras.

These are nations where a deep machismo prevails, and where these untenable and dangerous situations impinge on women’s physical and emotional lives, detracting from their opportunities in work and society.

Dona Dijé, collector of the Babassu nuts (Babaçu in Portuguese) that grow in the Amazon, and Dina Meza, Honduran journalist and defender of human rights, protesting against the Coup d’État that is taking place in her country, are two clear examples of very different fights in Latin American, in which brave women are taking the lead.

Brazil and the quebradeiras (Babassu nut-breakers)

300,000 women provide for their families in this country collecting and cracking nuts produced by the Babassu, a palm tree that grows on the sides of the Amazon river and produces a sought after oil.

The quebradeiras, as these women are known, have this tree as an only source of income. Nevertheless, today the Brazilian government is supporting economic activities to produce bio-fuels, mining and other full scale activities.

To tackle this problem, these women created a movement to defend their rights. One of its founders is Dona Dijé, a descendent of ancient slaves of the Maranhão region in the north of the country and quebradeira since the age of 16, is an example of the battle, and she shared her experience in an event organised by War on Want in London.

In this way, various small communities of working women have united their strength to create the Movement of Babassu Women Nut Crackers (MIQCB), to give a voice to this community, allowing them to improve their quality of life and avoid being marginalised.

In this way, various small communities of working women have united their strength to create the Movement of Babassu Women Nut Crackers (MIQCB), to give a voice to this community, allowing them to improve their quality of life and avoid being marginalised.

As Dona Dijé says: “It hasn’t been an easy fight. It is a long road and we have had to organise ourselves because they want to change our way of life.” Therefore, their first fight is focused on the right to own their land and have their work respected. They are also fighting for their rights to have access to healthcare and education. This is why they have decided to unite. The women’s movement has extended to the states of Piauí, Pará and Tocantins, also Maranhão, all in the northeast of Brazil. “We have achieved many things but there is still much more to do,” says Dona.

With the creation of this movement, these women decided to gain control of the entire process through co-operatives, from collection to the sale of the end product. But they also have to face another problem, deforestation. “If they cut down the Babassu forest we will have no income. We want to protect our environment, in every possible aspect. We don”t want to abandon our territory because we are intrinsically linked to it, each tree, each plant… and our children grow up free there.”

Dona, proud of her work, emphasises that “We are mothers, we look after our homes, we work, crack nuts and provide everything else for our families”. This work is what allows them to keep their homes and that is why they are fighting to defend their rights.

Dona, proud of her work, emphasises that “We are mothers, we look after our homes, we work, crack nuts and provide everything else for our families”. This work is what allows them to keep their homes and that is why they are fighting to defend their rights.

The Honduran Coup d’État

The fight for human rights and women in particular, has a prominent role in Honduras. The Central American country has been living in constitutional crisis since 2009. This, as the Honduran journalist Dina Meza states, had been planned by the most powerful groups of the country, formed by 10 influential families such as The Facussé, The Andonie and The Canahuati families, among others, with the support of The United States.

According to Meza, the oligarchy was annoyed by the small changes introduced by the previous government and decided to take control of the country. Since then, they have sold rivers and other natural resources to transnational corporations.

This has allowed them to keep more than 80% of the nation’s wealth. “Honduras is in its current state not because is a poor country but because it has been impoverished by the 10 families that misgovern the country,” she says.

In the same way, the journalist says that damaging laws have been approved against human rights and workers, controlling communications and militarising the country, allowing the building of US bases in Honduras.

In the same way, the journalist says that damaging laws have been approved against human rights and workers, controlling communications and militarising the country, allowing the building of US bases in Honduras.

Even so, they have found resistance. The strongest coming from women. “Despite the male chauvinism and patriarchal system that wants us in our houses, being mistreated, alone and in silence, with the coup happening on our doorsteps, we have been able to go out onto the streets,” says Dina Meza. “The military and the police insult us, denigrate us and call us prostitutes. But that doesn’t stop us.” They are workers, maquila workers, peasants, professionals and defenders of human rights, who confront them despite being the victims of “rape, persecution and harassment”.

“When the coup began, the military used to bring condoms to rape women”, points out Dina. “We want to fight. History has been built with our fights. The problem is that we don’t write it and that’s why we do not appear in it.”

Dina, who is in England as a result of persecution, highlights the fight of peasant women against the landowner Miguel Facussé in Zacate Grande and Bajo Agúan.

Even when “they watch over us, persecute us and insult us, women’s courage goes beyond all that. We want a Constituent National Assembly. We have to change our country”, she declares.

Even when “they watch over us, persecute us and insult us, women’s courage goes beyond all that. We want a Constituent National Assembly. We have to change our country”, she declares.

She also says she is not scared. “My only fear is not being able to participate because I couldn’t say to my children that I did nothing to try and solve this problem. That would be even worse than getting a bullet from the military.”

(Translated by Evelyn Dench – Email: edench75@gmail.com) – Photos: Pixabay

.jpg)